Overview

Procedural generation implies the production of new content based off of certain factors not unilaterally explicitly indicated by any individual. As computers are inherently deterministic systems, it follows that the sole way to produce undefined outcomes is to introduce randomness or noise into generation. This law is ubiquitous, notwithstanding of procedural terrain generation but found in all computer-related fields, notably machine-learning. As such, procedural terrain generation most commonly refers to the derivation of surface-terrain from a series of noise maps which dictate specific features of production.

Although this specific approach is undoubtedly effective for open largely unpredictable terrain, it lacks in reproducibility of certain strictly well-defined patterns which extends from the predictability of certain notable features observed in reality. Such features include trees, rocks, shrubbery, logs, vegetation, or given the specific application desired, roads, buildings, objects, spacecrafts, obelisks all fall under this umbrella.

While it is not impossible to layer noise maps to create specific shapes, and isolate these shapes to stepped noise regions, such an implementation is so unconventional and impractical that apart from extraordinarily unique cases should not even be considered. Another option is to isolate such patterns from procedural generation entirely in both in-game representation and storage, such as replicating a mesh procedurally after each chunk generation, and storing these meshes as individual elements appending the scalar fields used to construct the rest of the chunk. For confined games where further abstraction is unnecessary and unaffordable, this is often the chosen approach. Nonetheless, such an implementation implies a fundamental difference in these patterns in representation and handling even when such dilineation is intrinsicly superficial. In such cases a unified system that does not differentiate such patterns following generation is to be desired.

Background

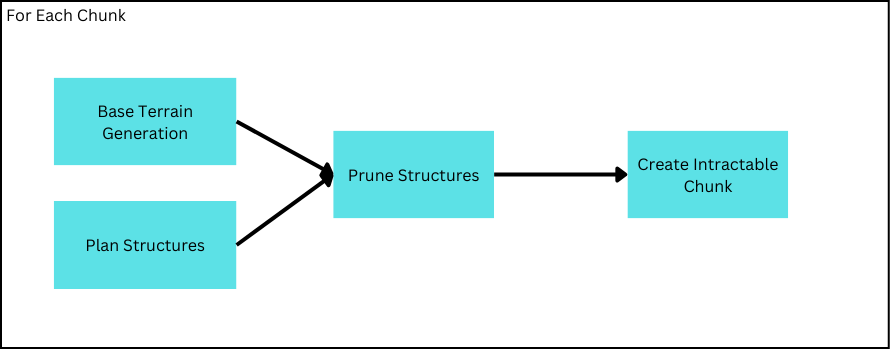

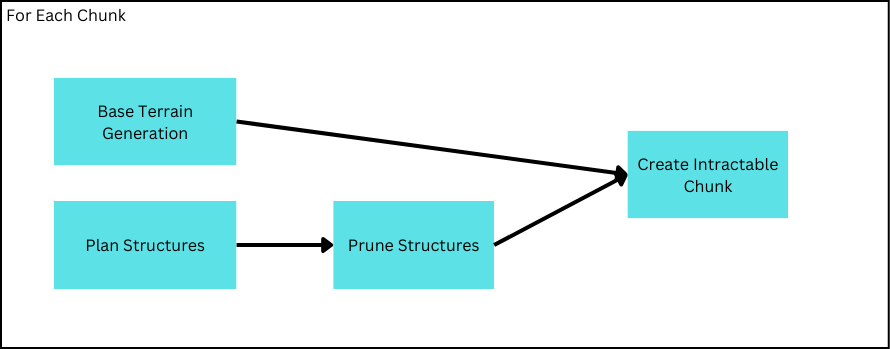

Previously, the problem of structure generation was subdivided into planning and placement stages to enforce chunk-centric generation–and while the proposed solution for origin-sampling does address the most pertinant issue in structure planning, it alone does not account for the entire planning process. In fact, it scarcely accounts for much of the workload necessary to completely plan a structure. Rather, structure-pruning represents another crucial and expensive component of structure-generation which, though conceptually easier to grasp, presents much to be desired and even more room for improvement.

Currently, Structure-Planning purports to assign structures by their size held in direct relation to the level of detail, or the amount of points sampled from an area; yet while the sampling detail-level can be ascertained, the critical link of actually assigning structures is still unresolved. In the preceding article the analogy of deconstructing an infinite assemblance of varying structures into a point-cloud would suggest this link be merely the reverse of this process. But taken literally, this might trick one into believing that every structure must have a uniform probability of appearing everywhere where in reality patterns tend to appear depending on a strict assortment of factors.

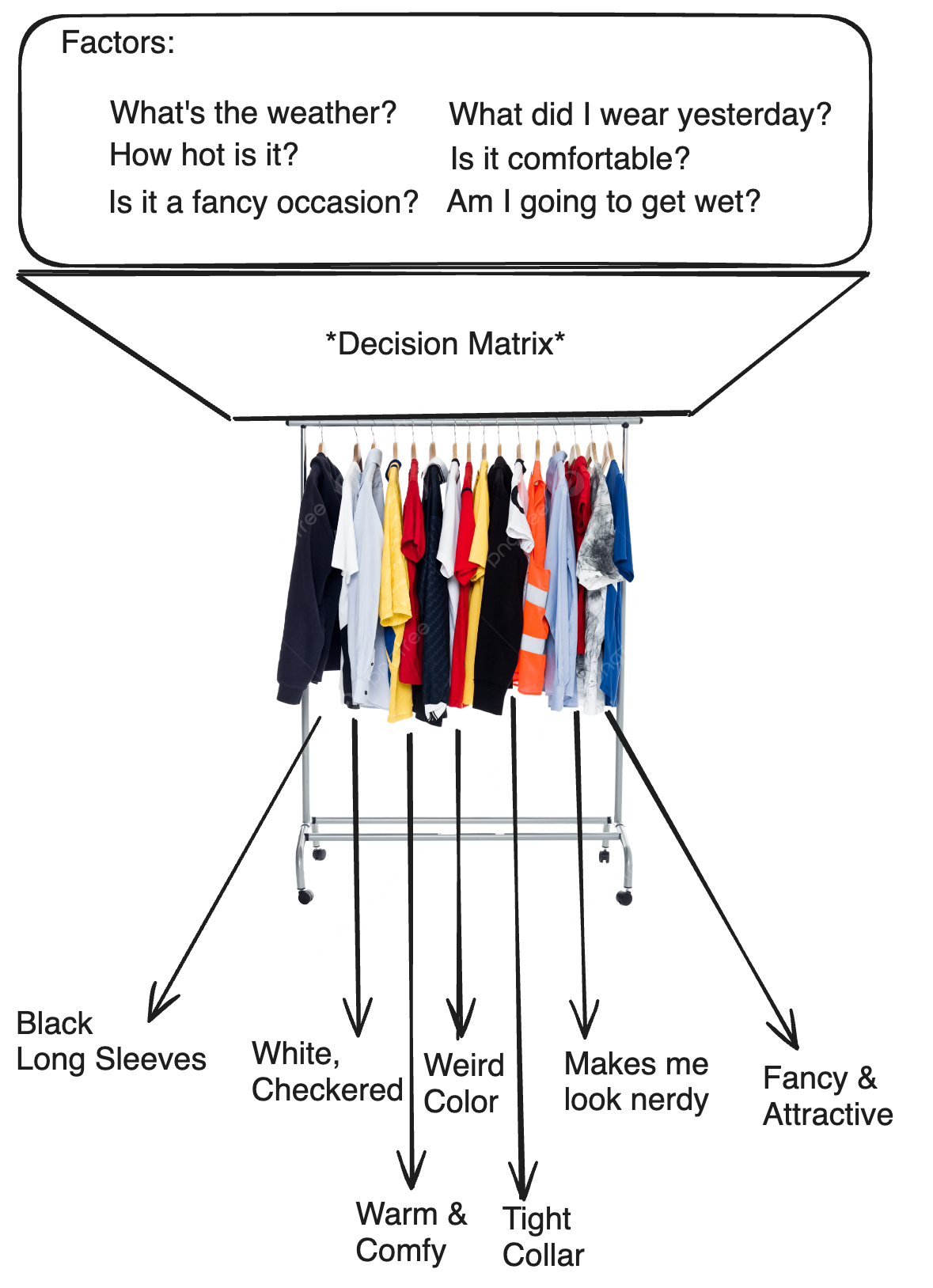

Colloquially, procedural terrain generation commonly organizes such factors into categories known as biomes, where factors dictating terrain generation can be used to evaluate a region’s biome, which may then be used to assign different attributes to the terrain. You can think of this like a wardrobe.

Often, factors used to decide the biome effect the actual shape of the ground while biomes assign attributes describing the apperance & properties of the terrain–this allows for the terrain shape to be continuous while disjointed biomes can generalize more superificial properties. This will be investigated in a further article. For the purpose of structure-assignment, biomes provide an accessible category to organize structure-assignment without programming individual placement patterns for every structure.

Specifications

Coming back to the same central requirements, there is a need above all else for this system to be deterministic. As described before, each chunk is not only responsible for planning structures generated within its bounds, but for identifying structures in nearby chunks. Two chunks must assign the same structure to the same origin without communicating with each other and for this reason, structure assignment must also be deterministic.

Solution

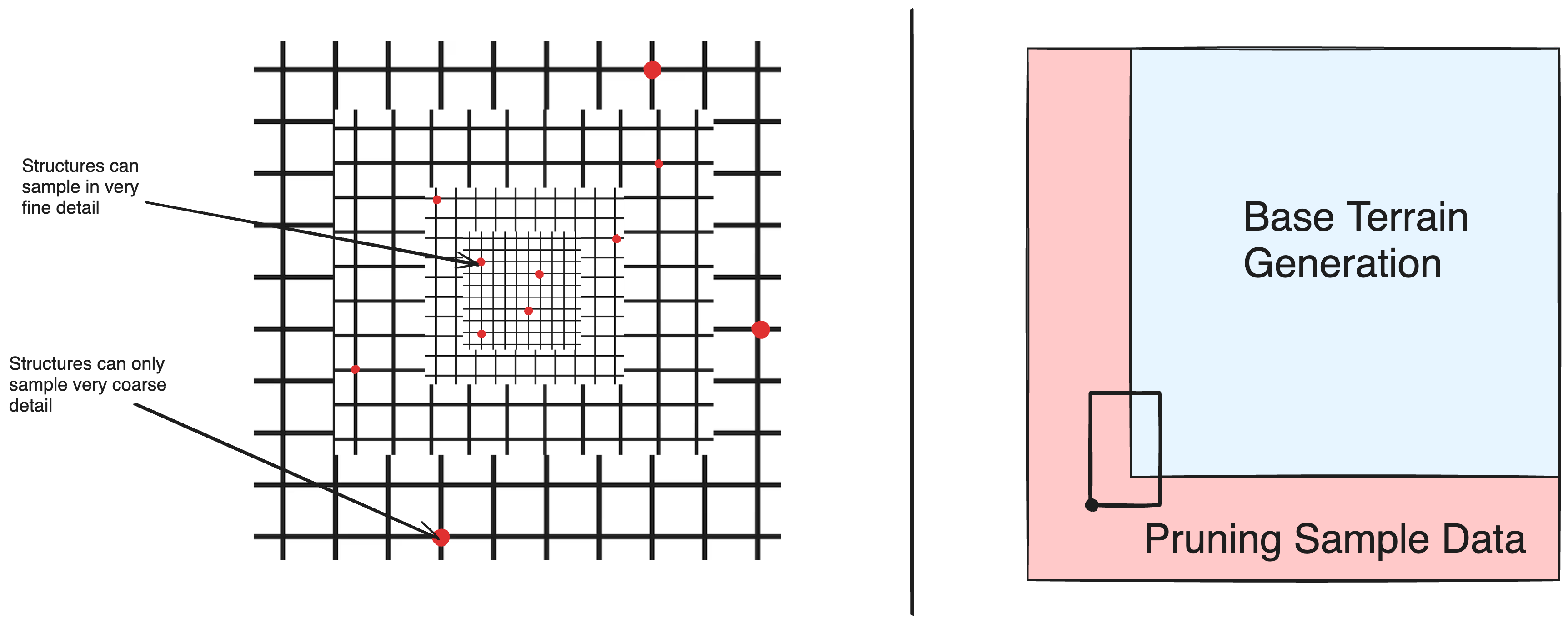

When pruning strucutres it is necessary to sample information about the base terrain. Even solely considering biomes, a planned-origin must at the very least be able to sample its biome to determine which group of structures to consider. Here the implementation will branch between two methods I will describe as prescreptive and descriptive pruning. The “scriptive” in this instance refers to the availability of the terrain information(such as biomes) which dictates the method of sampling said information.

Descriptive

Perhaps the most widely adopted method, descriptive sampling involves the prior procurment of the base terrain information. In effect, this means

When specifically structure-planning occurs is not absolute, but one may prefer planning directly before pruning as to consolidate structure generation into a single step.

In line with its popularity, this method provides undeniable advantages. Primarily, as “Base Terrain Generation” is an innevitable step, prior procurment is no more inefficient than postponing it until after. On the other hand, it can drastically simplify structure placement as querying information relavent to structure pruning may be reduced to simply determining the location of the cached information rather than on-demand evaluation from the underlying noise algorithms.

While it makes sense that, if we’re going to evaluate the base terrain anyways, we should reuse that information when possible, there are several underlying limitations. Often, extremely expansive terrain is produced through the use of levels of details, which simplifies distant terrain by skipping progressively coarser calculations. Unfortunately, these fine calculations may be pertinent to structure pruning and relegates the process to either admit a certain level of coarseness or an inversely proporitional distance of generation. Even foregoing applications with levels of detail, allowing each chunk to identify structures outside its boundaries necessitates a further region that must still be computed just to supply data to structures placed outside of generated chunks.

Moreover, if there exists data essential to structure planning but utterly superficial in all other aspects after generation(biomes in this case), it must be persisted solely for this purpose.

Prescriptive

Contrastingly, prescriptive procures procures terrain data on-demand, and thus makes no discernment as to when in relation to base generation it must occur.

Prescriptive sampling attempts to procure on-demand terrain information by performing the role of Base Terrain Generation for every sample and thus has the obvious disadvantage of being much slower. Furthermore, it is arguably less scalable than descriptive sampling as any changes to Base Terrain Generation must be reflected in the sampling method whilst further complication on its part will be inherited. Meanwhile, prescriptive sampling has the undeniable advantage of not being limited by the extents of base generation; as it is entrusted to construct the output by itself, it matters not if the sample is outside workable-chunks or of extreme detail. For contained terrain generation algorithms, the freedom Prescriptive sampling provides is an invaluable tool for structure-pruning.

Identification

In any case, since biomes are used to signify a group of structures in this case, there is the need to identify specifically which structure to assign to the origin within this group. Returning to Structure-Planning, an origin is supposed to assign sizes in correspondence to the LoD it is sampled at, so instincutally we can assign a structure by searching through all structures for the largest structure of a designated size-LoD less than or equal to the sample LoD.

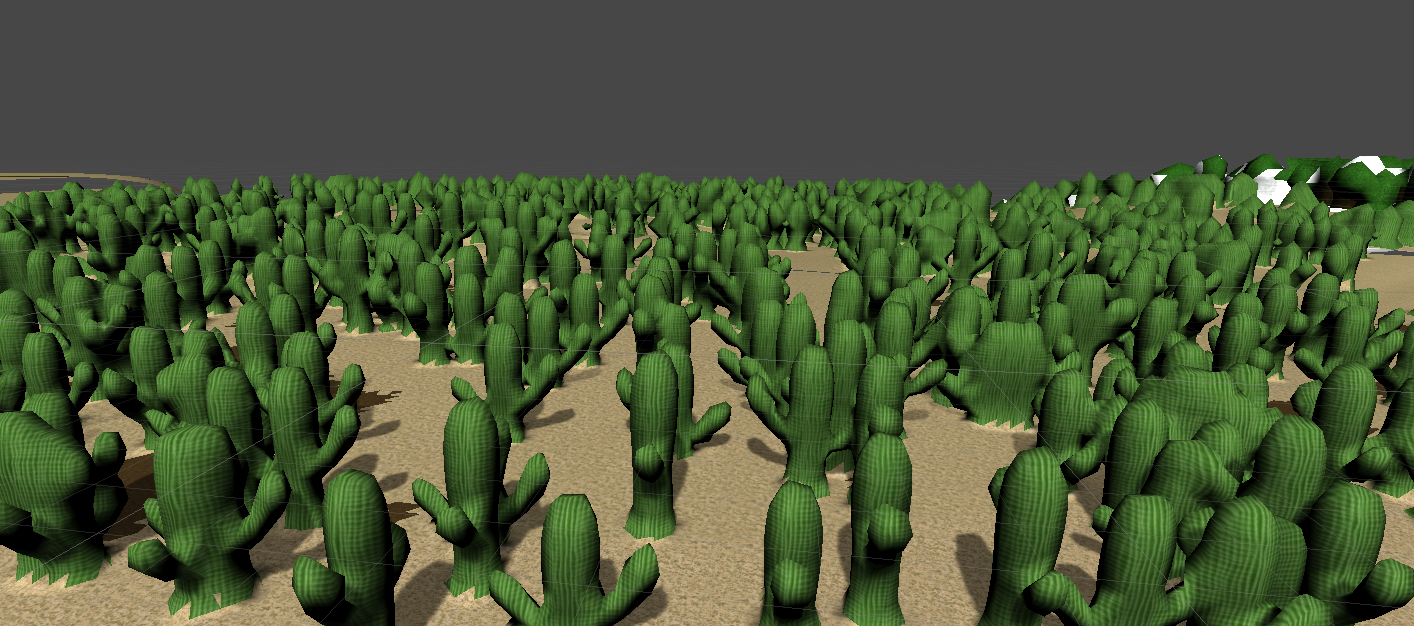

Good, but that’s a lot of cactus, it’d be better if we were able to not use all of the origins structure-planning gives us, but be able to throw away a percentage of them based on the structure being applied. To discard a percentage of origins being assigned as cactus, a random number 0->1 can be generated and tested against a preset “generation frequency” of the assigned structure. However, to ensure that two chunks processing the same origin both identify the existence of the structure, this random number must be deterministic as well. Luckily, we can apply the same strategy used in Structure-Planning of using the position of the origin as a seed, since it would be the same as previously guaranteed. The origin position will now-on be used as the seed for all future random operations.

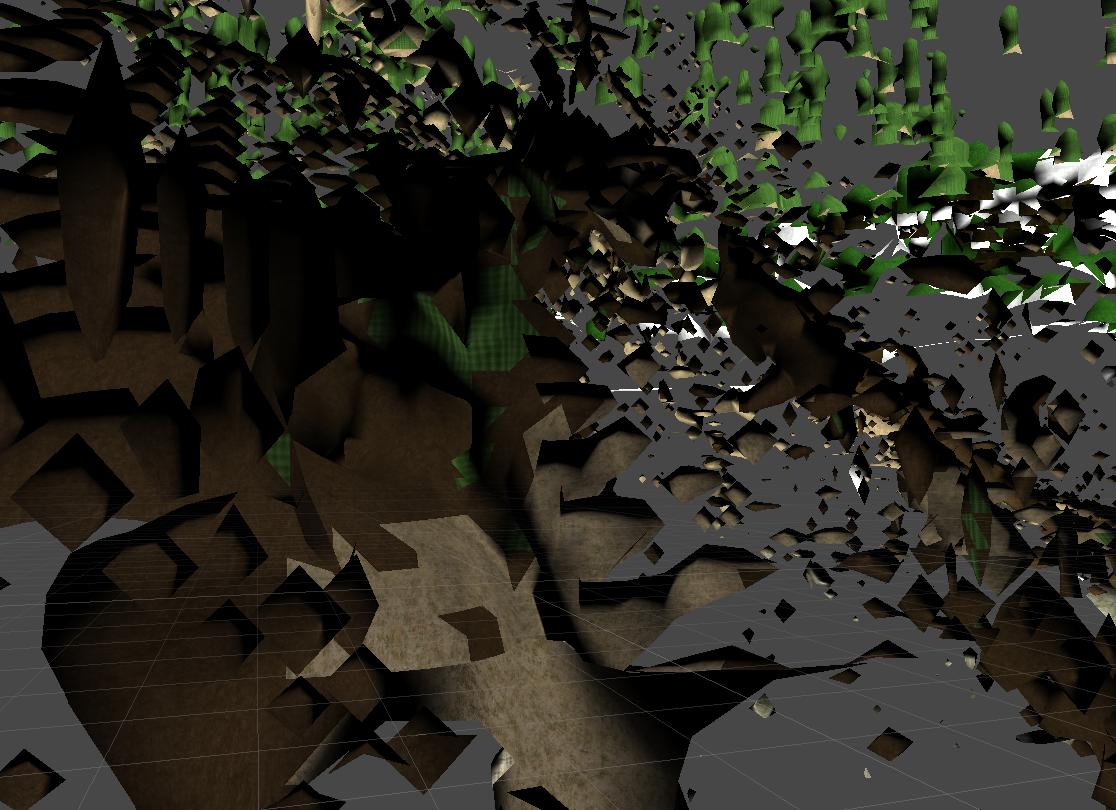

Applying this, we see that structures are being generated in caves as well.

This is because, in many applications Biomes are constructed off 2D noise maps and consequently 2D maps themselves. Thus, structure organization is bound by these limitations and extend infinitely vertically. The reason biomes tend to be 2D in most games is that biomes are inherently characteristic at their surfaces, which are 2D for the most part and similarly encapsulated by 2D noise. That is not to say 3D biomes are impossible: Minecraft, a popular procedurally generated game blends a variety of 3D and 2D biomes to leverage cave and surface features. But even for Minecraft it is not difficult to say that 2D Biomes is undeniably more expected–partially because we all live on the surface of our world.

As a consequence, biomes in procedural terrain are often also considered to be 2D, and thus there is no grouping for structures vertically. A possible solution is to compensate for vertical grouping by assigning a unique falloff curve for every structure, given the distance to the surface (This can be the same method used for materials as well). Structures meant to be placed underground can define curves that falloff slower underground while surface structures can falloff dramatically.

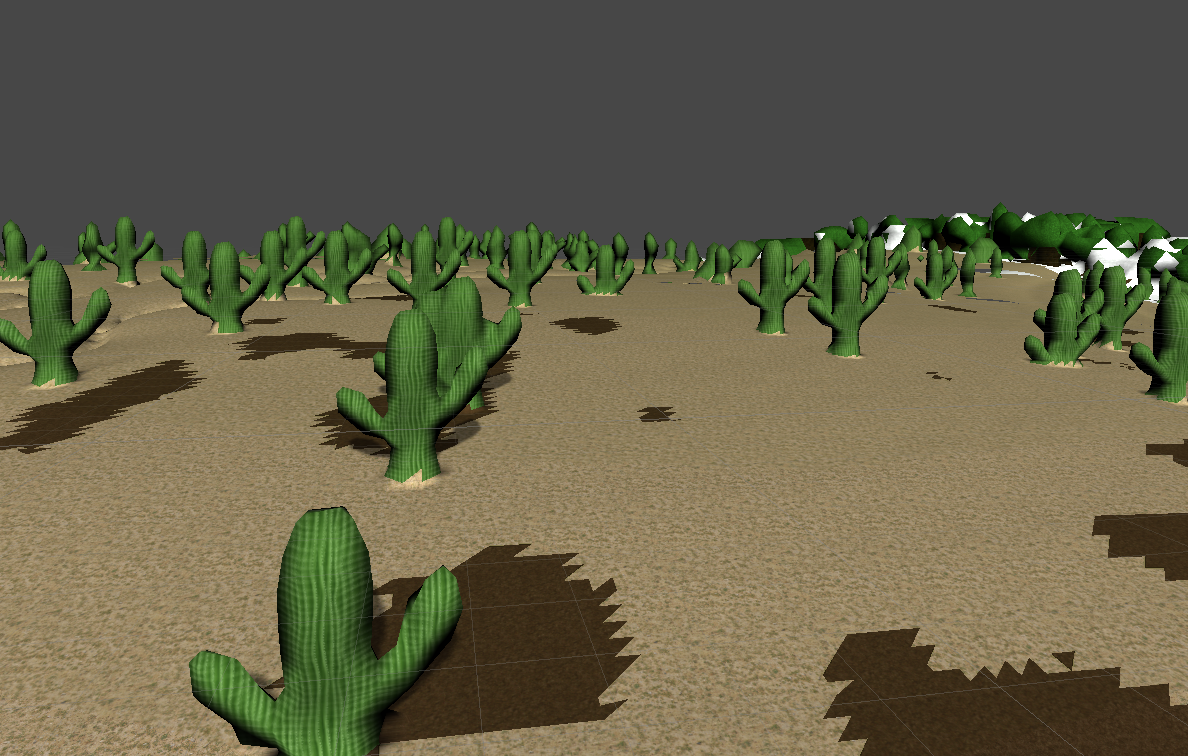

Wait a second, these are all the same cactus! Because every cactus is around the same size, they are the same sample-LoD–but given our specification that we choose the largest structure with a sample-LoD less than the origin sample-LoD, all origins innevitably choose the same structure. To resolve this, we can reuse the discarded(pruned) percentage of origins by allowing them to reassign to a different structure. This allows us to conserve the origins provided by the planning step and, in parallel execution, conserve threads that would have otherwise terminated once their structures were pruned.

This may be further accelerated if “generation frequency” sums to 1 for every LoD, such that a prefix sum can be constructed. Hence, one is simply able to binary search for the range of structures with the same LoD, and then search again for the largest prefix entry smaller than our random number.

Pruning

There’s a problem we’ve been avoiding up until now–a problem often encountered when placing structures.

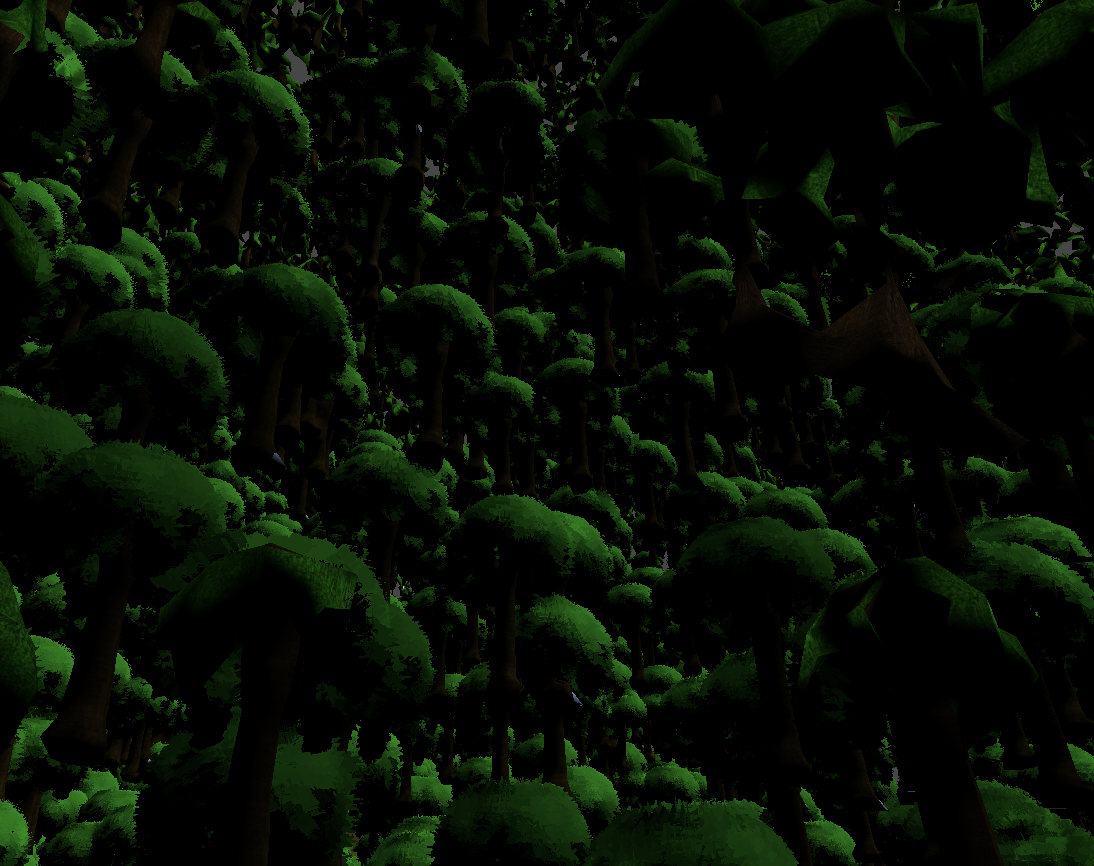

All the trees are floating! Of course, we can slightly mitigate this issue by increasing the surface-distance falloff factor discussed before, but even if we limit structures to only generate underground, there is no guarantee that the trees won’t be floating inside a cave. Instead, we need a way to check if trees are anchored to the ground and prune away the rest.

The check system is represented through a series of positions represented as 3D offsets from the sample origin. For every structure placed, each check position can be extrapolated from the origin and information about the terrain at the position is sampled. If the information at that position is within the boundaries of a preset desired range, then we can proceed with generating the strucutre, and prune all undesirable structures in which the check fails.

For instance, to generate a structure on the ground it is necessary to define two ‘checks’, one at the base of the tree and another at its trunk. At the base of the tree, we can specify that the density of the ground must be greater than a certain value (aka underground) and the trunk must be above that value (above ground). Thus, all structures whose base is not underground and trunk is above ground is pruned leaving just trees attached to the ground. Another check can be placed in the tree’s leaves to prevent it from generating into a small cave with just its trunk visible.

Compartatively, there exists methods to plan structures and then adhere them to the ground which may be able to conserve more structure points than pruning. But pruning is unparalleled in its flexibility–for structures placed in the air, or need to be attached to the ground at multiple positions, there is no need to design new algorithms to find these features, just an additional check is enough to eliminate all structures except ones placed with those specifications.

Variation

There is one last issue to address. Currently, structures are defined and placed with a static orientation, all trees constructed from the same structure will look identical: facing the one direction that it is defined to face (See 3rd Cactus Diagram). To allow structures to be placed facing various directions it is trivial to simply copy the structure definition in other directions, but such a method would be memory exauhstive. Rather, it would be far more efficient to allow certain structures to be rotated when placed.

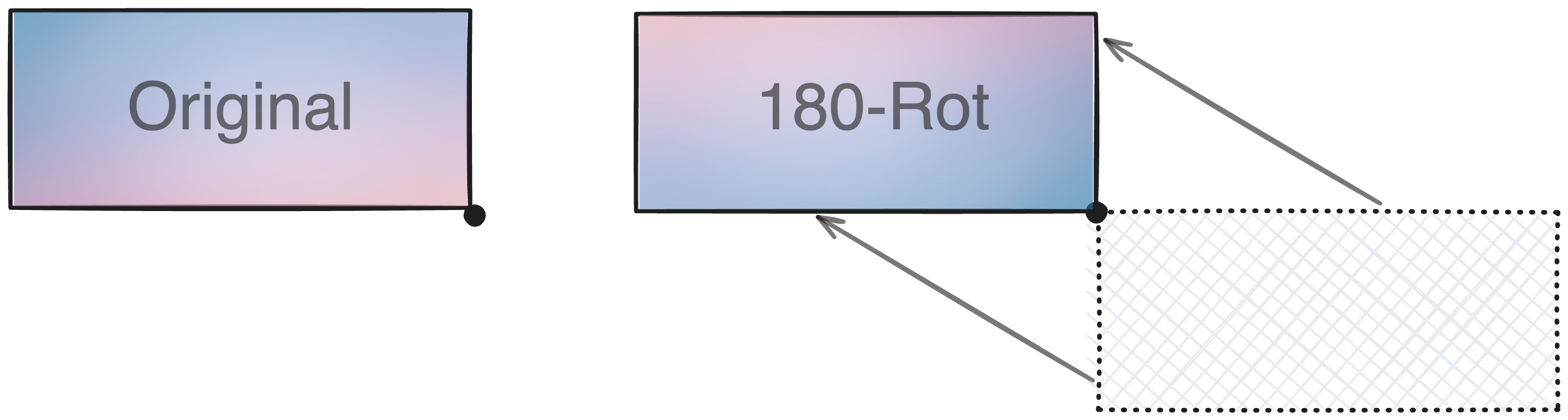

Firstly, while we mention rotational variation, such variation must be limited to multiples of 90o as generation is inherently grid aligned and any other rotations would result in massive complications. Thus, with only 90o rotations, there is a total of 12 unique rotations: using spherical notation, 4 theta rots * 3 phi rots. Of course we probably don’t want an upside down or fallen down tree, so phi rotations and theta rotations should be seperated and independently togglable. As we are only dealing with 12 rotations now, it is feasible to define a lookup-table for matricies representing each transformation. Such rotations would need to be applied to checks as well.

A final thing to consider is that, given the definition of a structure origin as the bottom corner of a structure which simplifies structure planning, the origin must not be rotated–instead the entire structure must be shifted to recognize the new corner as the origin. Concurrently the extrapolation of each point from the origin must adapt to this change.

Code Source

Optimized HLSL Parallel Implementation

1 |

|