Overview

Memory Management is a problem ubiquitous to practically all fields of Computer Science. Concurrently, many optimal solutions are built in to either the development environment or OS itself so that the average high-level developer does not need to concern themselves with it. Nevertheless, an understanding of memory management is helpful when optimizing the space, and even time, complexity of different systems.

For the most part, I will be discussing unique/interesting techniques in memory management I’ve employed in the development of this project. Memory management is a broad concept often evaluated in framework development, and physical memory allocation is a seperate topic in Operating Systems. Both are extremely complex, abstractified, and irrelevant in many high-level discussions. While a deep-dive into the topic is avoided, several points may be made referencing the existing architechture only as background or justification.

Background

All programs must use program memory, and most programs use data memory (barring calculations small enough to be contained in registers & caches and don’t request addresses). Data memory is commonly divided into two logical structures, a stack and heap, which are optimized for two unique use cases: sequential(alloc is LIFO) access of data allocation and release(handling), and random access handling.

While most developers are aware of these concepts, few must concern themselves with its implementation. Such low-level memory organization is such a fundamental hurdle that the best optimized solutions are already built-in to most kernels. However, as most OS operate on the CPU, data management often is funneled through the CPU even when the data is not to be processed by it. This proves to be a significant obstacle for extended programs running on devices that cannot communicate easily with the CPU, in this case shader code executing on the graphics chip.

As most shader operations are highly parallelized, sharing memory quickly becomes very complicated so direct memory handling is commonly frowned upon. Instead, when data memory is required(e.g. the output color to the screen), resources are most commonly handled in the CPU and bound to the shader processes. This works for most contained modular tasks(admittedly what the GPU is built for), but creates a serious issue for extended operations. Operations which generate unpredictable amounts of data may find that resources bound to it are insufficient; furthermore, as shader-code isn’t designed to interrupt the CPU, memory reallocation requires the CPU to be constantly listening for such cases, which is infeasible if only due to the synchronization delays required by the GPU. Consequentally for these cases, it is common that significant resources are wasted in supplying the maximum tolerance so that overflow is impossible.

While this approach is acceptable for short-lived resources(commonly frame-temporary), for long-term storage of data it permanently ties down excess resources eventually leading to significant accumulation of waste. One solution could be for any shader task responsible for creating an unpredictable amount of data to first copy to a maximum tolerance buffer. The CPU may then readback the actual size of the data generated to allocate a perfect-fit permanent buffer for the data allowing the GPU to copy the cached data from the first buffer to the second. While this seems wasteful due to a second pass to copy from our cached location to storage, in practice the most significant drawback is reading back the size of the data.

The reason for this is complicated. Many believe that this is because it is costly to halt execution across all GPU threads to ensure consistent data can be read. In fact, the real reason is because CPU-render commands are not immediately executed but instead buffered while the GPU completes them at its own pace. Thus, to readback data, it’s necessary to stall the CPU while the GPU ‘catches up‘ on the commands it is buffering. Constant readbacks, in a sense tie the CPU and GPU together, reducing parallelization between the processors so that delays in either slows the other down.

Therefore, to reduce resource waste, a better strategy is to consolidate the buffers into a singular memory block(like a memory page allocated for a management system) that can be managed independent of CPU execution. This can be achieved through a custom memory-management system executable through shader code so it may be buffered into the GPU’s execution. Doing so allows consolidation of all wasted tolerance into a single location, greatly reducing chance of overflow and creating a single location that can be monitored by the CPU.

Thus, for long-term storage of GPU generated data, the implementation of a custom, shader executable memory-managment system is necessary.

Example Use-Case

Polygons generated through marching cubes by shaders are hard to predict from the CPU. Reallocating a buffer from the CPU would stall the CPU while the GPU catches up on commands. This system intends to solve this by creating comands able to be buffered as a GPU instruction maintaining parallelization between the two processors.

Specifications

Just now I mentioned that consolidation of memory can reduce chance of overflow, but the reason for this may be subtle to some(I use ‘overflow’ to refer to the case where not enough memory is allocated for the data generated by our shader task). If data is stored in multiple seperate buffers allocated to be of maximum tolerance(overflow impossible) where the chance of using the entire block is C0, C1, C2. . ., Ck where 0 ≤ Ci ≤ 1, then the minimum chance of any overflow occuring when using smaller sized buffers is max(C0, C1, . . . Ck). However, by consolidating all the maximum tolerance buffers into one block, the chance of using the entire memory block is instead C0 * C1 * C2 . . . * Ck, meaning the size of this block can be reduced with a much lower chance of overflow.

One reason why shaders aren’t allowed to allocate their own memory is that they are built to be parallelized; multiple threads are built to execute the same instructions such that a single memory allocate instruction could inadvertently allocate multiple memory blocks, one for each thread reading it. In compute shaders, threads can often by distinguished by a thread id which can be used to designate a single thread responsible for handling memory. But as the other threads are just idling, a simpler method is to specify the compute shader execute on a single thread.

This is rather unintuitive, the GPU is built for parallel execution–synchronous tasks should usually be completed on the CPU. It could be said that during our synchronous task the GPU is not using its full potential and as such, we want to minimize the amount of time spent on this suboptimal command. For example, many high-level languages feature algorithms(Garbage Collection) that constantly rearrange memory based on how long they exist, their size, and compression amongst other factors. This is undesirable for us as it would require the GPU to constantly halt parallel execution for slower synchronous processes. We ideally want a system with a little maintenance as possible.

Solution

I want to clarify that for the purpose of simplicity, this system will be designed to handle memory blocks in units of 4 bytes. Shaders do not have great support for 2-byte precision types and it is rare a single byte type will be used; in most applications, 4-bytes represents the smallest unit one will deal with. Additionally, I will refer to a unit of 4-bytes as a Word. A Word is a name for the “fixed-sized datum handled as a unit by the instruction set“Wikepedia, which in our customly defined system’s instruction set will be 4 bytes.

Basic Allocation

Let’s focus on allocation of memory for now. An allocation call can be specified like so.

1 | uint Allocate(uint size) |

The function should take in the size of the memory block that we want to allocate and return a pointer to the address of the block that has been allocated. As shaders don’t allow pointers, this can just be a number representing the index inside a UAV buffer.

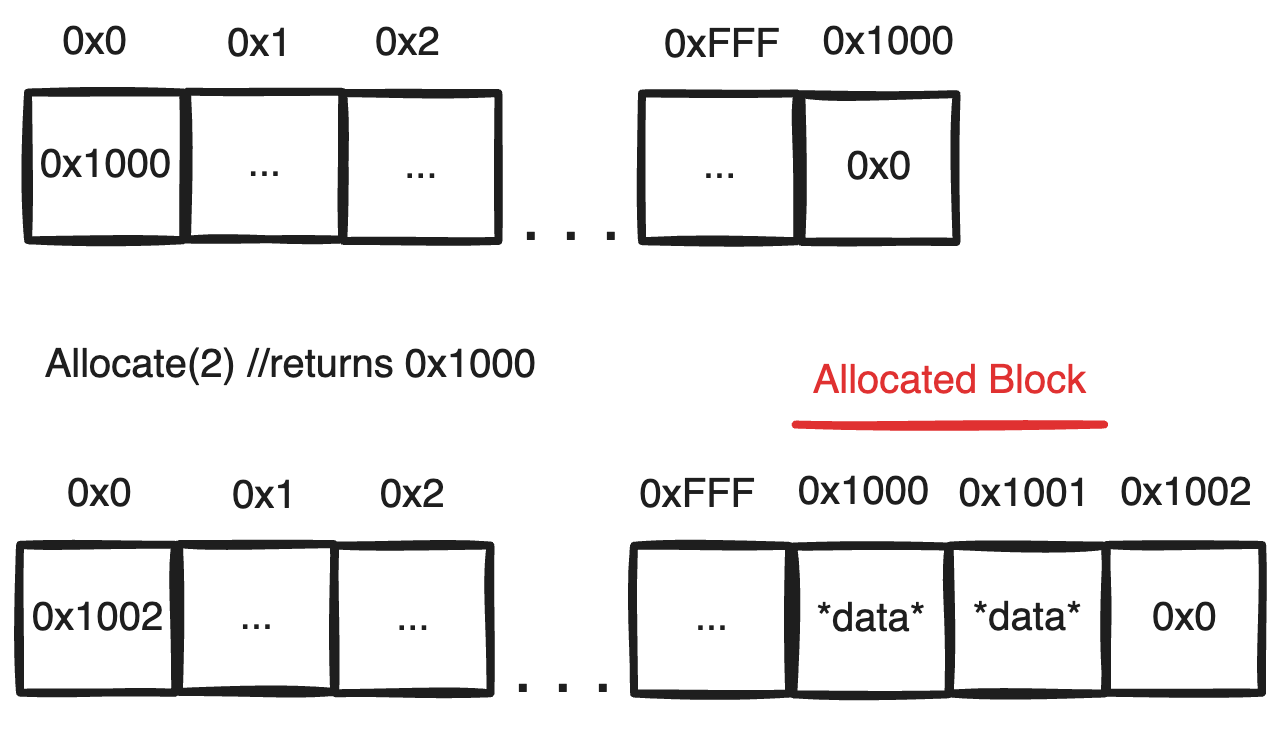

Now comes the first challenge, finding a valid block of the desired size. If we give a random index, this may cause the block to extend OOB(out-of-bounds) or intersect with another allocated memory block. If the latter happens, this will overwrite the data in the original memory block thus corrupting its data; guaranteeing data integrity means preserving no blocks intersect. To do this, we can keep track of the index of the last position allocated to allocate the next consecutive block immediately after. This last allocated index or first free index can be stored in the beginning of our buffer which we can designate as special metadata.

As each block is put immediately after the last allocated block, we can guarantee that no block can intersect with any pre-existing block. As more data is added, our ‘free-index‘ pointer continuously increases pushing the data farther and farther down the buffer. If we had an infinite buffer, this would work perfectly. But we don’t so eventually, the pointer will reach the end of the buffer at which point we have no way of knowing where a free-block can be found even if enough memory has been freed to create one.

Basic Free

To learn how to recover this used memory, we have to first define how we free a memory block.

1 | void Free(uint address, uint size) |

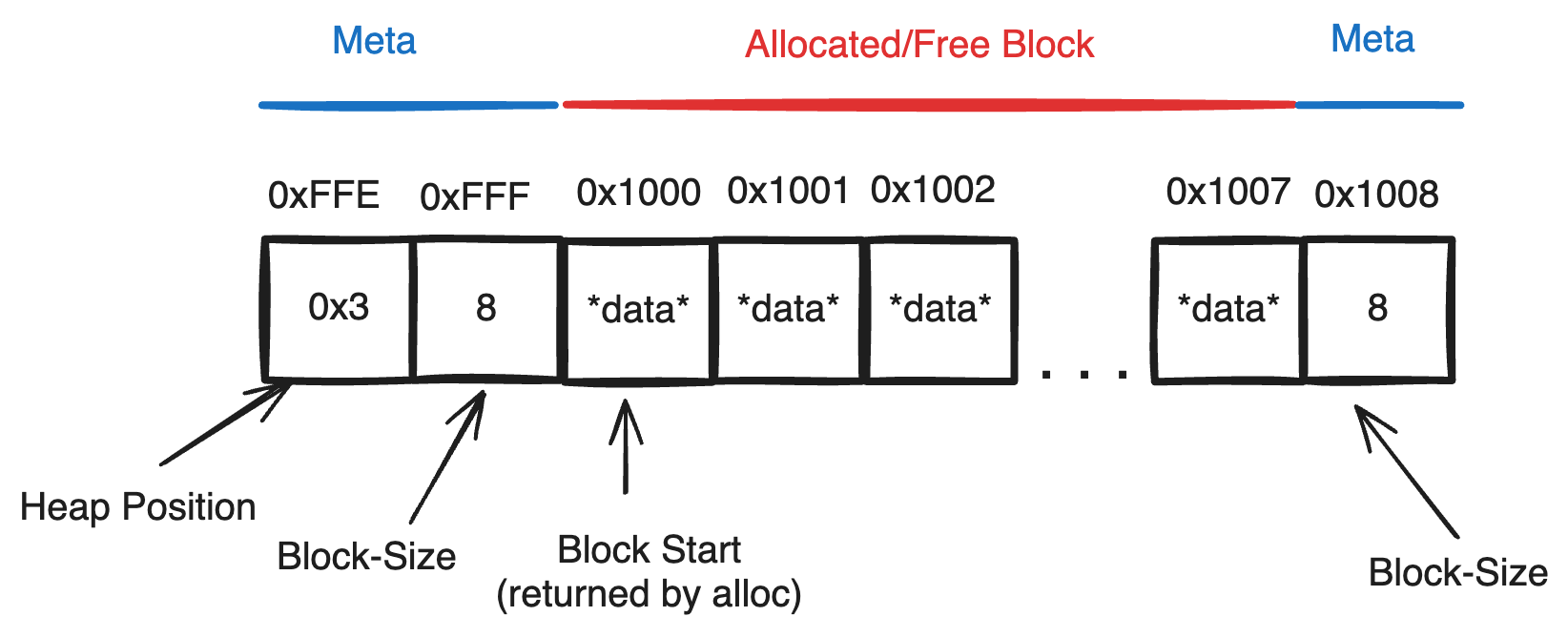

To free a memory block, we need to know the address of the data being freed. Right now, we also need to specify the size of the data we need to free as there is no way of determining how much data was allocated at the address. This is sub-optimal, as normally one expects to free the same block they allocate, and thus this function should assume it only recieves addresses returned by ‘Allocate‘(i.e. contiguous memory blocks) and the size to free should be the size that was allocated at the address. To achieve this, we have to also store the size of every block along with each allocation. This can be done with some special metadata prepending every allocated block.

Note: Address Pointers to Open Blocks should point to the first mutable position in the block. Nonmutable meta-data will be placed before the returned address and the size of a block will be alloc_size + meta_size where meta_size is the same for every block

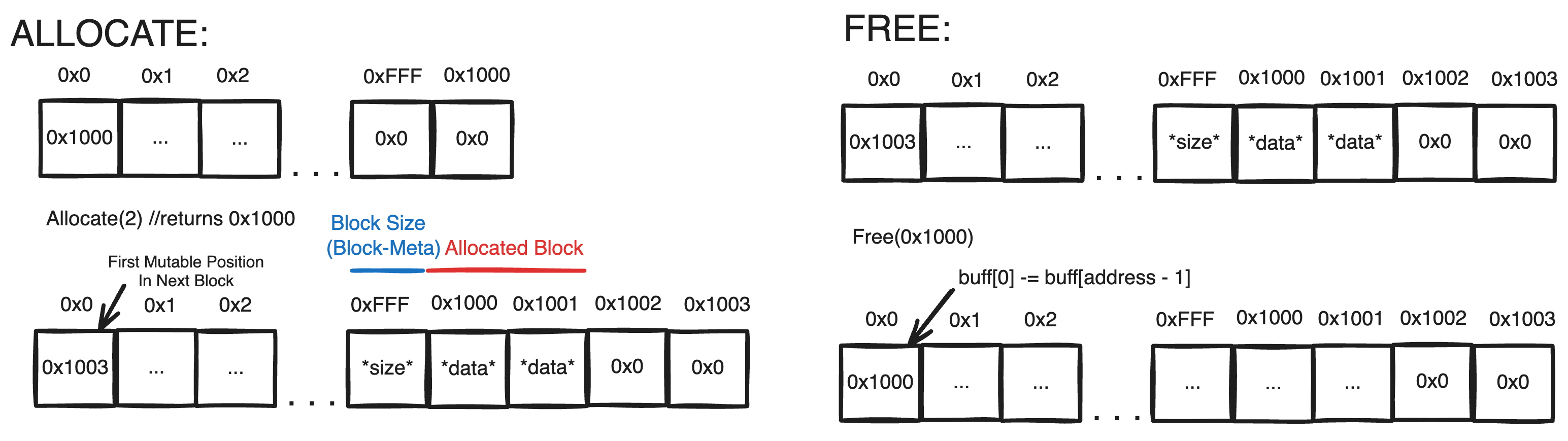

This works if memory blocks are deallocated in the same order they are allocated, but if they aren’t (as is possible in a random access handling system), a single pointer will lose track of memory blocks after the last freed address. One way to get around this is to keep track of freed blocks in a free-list where each entry contains two integers detailing the address of the freed memory block and the size that is free at that location. Then to allocate memory, one needs to search through the list for a ‘freed-block’ large enough to contain the allocation. Initially, this list may hold one entry whose size is the entire buffer.

This may currently seem redundant as size already is stored in the block’s metadata, but the reason for this becomes clear when discussing the Heap

Heap

A memory heap is unrelated to the heap data-structure, it is in fact just a word for ‘data managed for random access handling’ or a heap(pile) of data. It is a catch-all name for many different implementations and several layers of abstraction in charge of actual(or at least virtual) memory management. More Information can be found here. However a heap-data structure is unexpectedly useful in our memory heap.

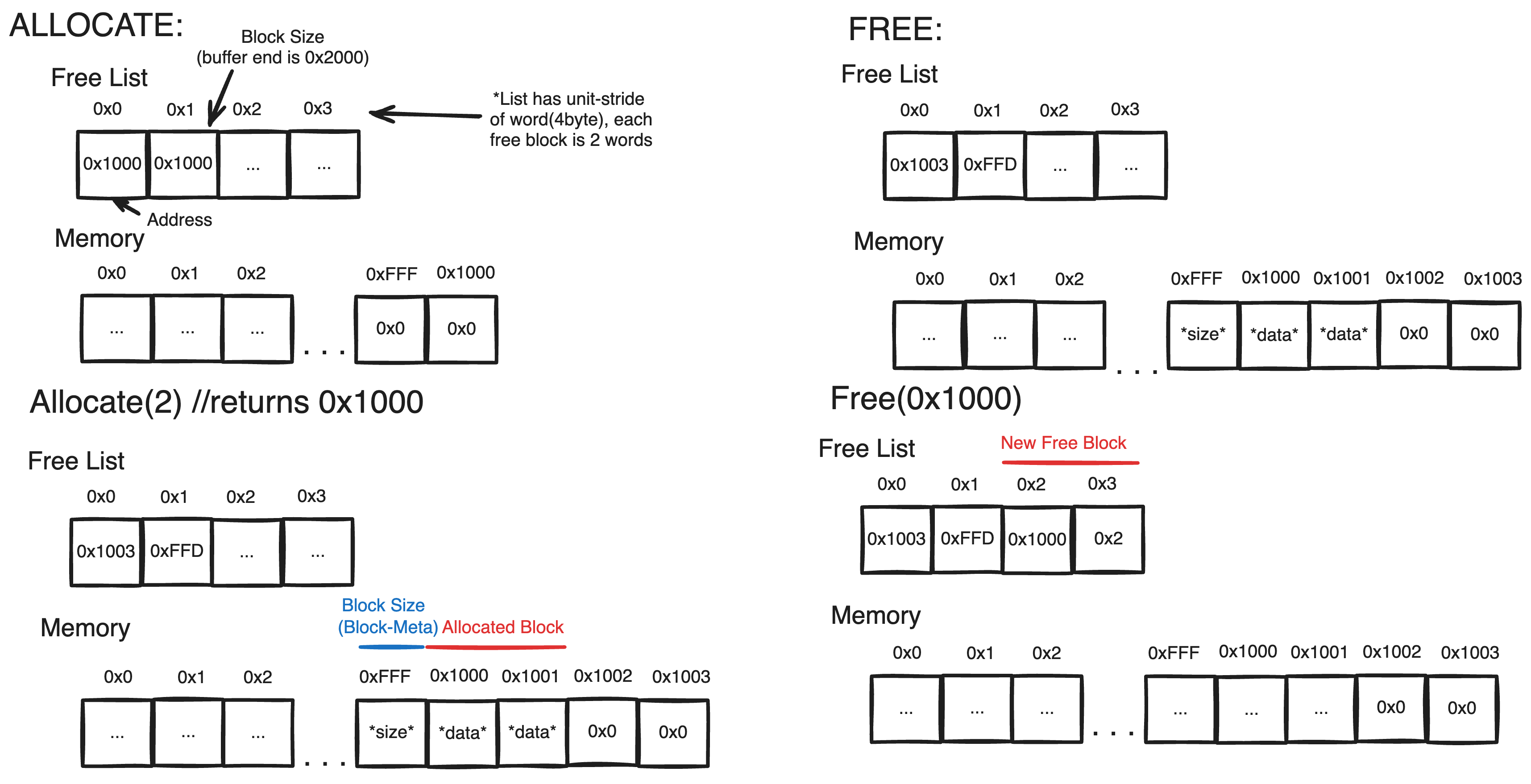

As of now, the free-list is not sorted in any way–it just so happens that most of the buffer hasn’t been populated so the initial block is still the largest. As more blocks are allocated and freed this property will degrade. To allocate a new block, it is necessary to find a free-block from the free-list capable of holding the block(i.e. free_size ≥ alloc_size). As we don’t know where this block is we have to search through all free-blocks to find it implying that allocation has a time complexity of O(N) where N is the amount of free-blocks.

Rather than a Free-List, a Free-Heap(a literal heap structure) which maximizes free-block size can guarantee that the largest block is always at the top, meaning that if there is enough space for a particular allocation, alloc_size must be smaller than the block-size at the top of the Free-Heap. This means allocation can be completed in logarithmic time(as you would need to sink the top). Meanwhile, Freeing a block is slightly more expensive as adding to the heap must also preserve the maximizing heap property, but it is also only logarithmic.

Fragmentation

There’s an obvious problem with this implementation. To allocate a memory block, a free-block larger than or equal to the memory size must be identified. If this free-block is of equal size to the desired alloc_size, then it can be allocated and the free-block removed from the heap. But most of the time, the free-block will be larger than alloc_size in which case we have to break up the free-block into two blocks: one that is of size alloc_size and the remainder free-area which is put back in the heap. The issue is that we’ve created two smaller blocks in a system where there is no operation to create larger blocks; free turns a same sized allocated block into a free block and allocate(likely) turns a larger sized free block into a smaller free block and allocated block.

With more usage, this will destruct the free-heap into smaller and smaller free-blocks even if the free-blocks may be adjacent to one another. This is a form of memory-fragmentation I will refer to as free-block fragmentation that continuously divides memory into smaller regions so that larger allocations become impossible even though there is physically enough contiguous space.

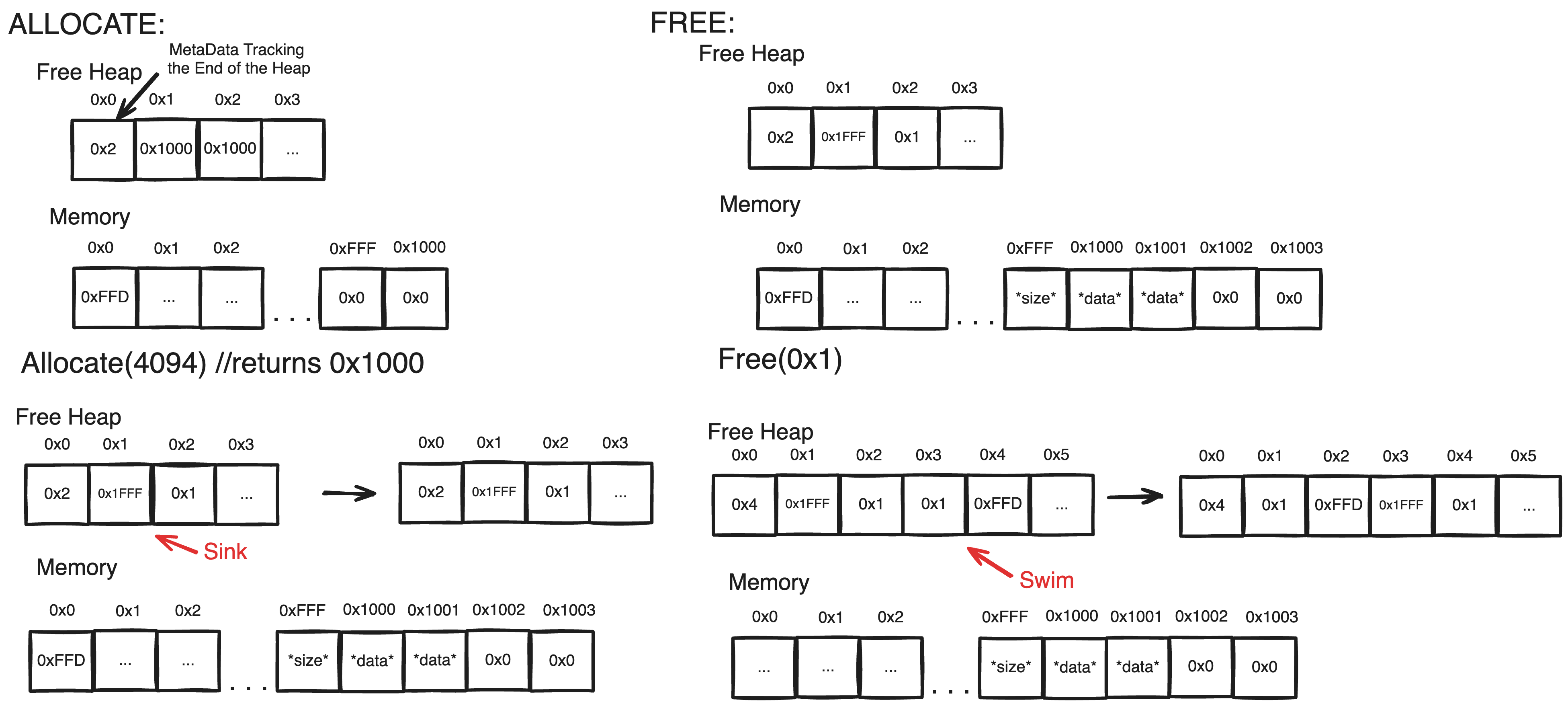

To rectify this issue, we need a system to create larger blocks from smaller blocks. As blocks have to be contiguous memory locations a larger block can only be created if two smaller blocks are adjacent to one another. In One-Dimensional Memory, each block has 2 neighbors(be that an allocated or free block) meaning that a block needs only to check two other blocks to identify all ways it can merge. These two neighbors can be described as the previous and next entries in a linked-list of consecutive block entries.

The word linked-list which refers to “a linear collection of data elements whose order is not given by their physical placement in memory”Wikipedia is a bit dubious in this situation. The order of blocks in our linked-list is consecutive in memory(‘given’ by memory placement), but it does not permit random index access as the location of an entry isn’t defined by its memory location relative to the start

As we need to identify both neighbors for every free-block this linked-list will be doubly linked so the previous and next consecutive memory blocks can be identified.

Linked List

The goal of our Linked-List is to merge together smaller blocks to counterract free-block fragmentation. A free-block is identified through its heap entry and likewise Merge in this situation effectively means replacing their heap entries with a larger heap entry that encapsulates both blocks. By this definition, only free-blocks can be merged as only free-blocks are stored/identifiable through the free-block heap. This also means we can maintain that allocated blocks are precisely the exact size that was requested since they will not be expanded.

To measure whether we’ve achieved our goal, we need a criteria which the algorithm must always maintain such that the system can be declared as functional. For this implementation, I will define this criteria as such: The algorithm succeeds and the memory is not fragmented if there are no two adjacent free-blocks. Furthermore, I will attempt to maintain this property without active memory maintenance; all memory reorganization(merging) must be directly connected to calls to ‘allocate’ or ‘free’.

This seems like a tall order, but the solution is suprisingly simple. Two adjacent free-blocks are only created when memory is freed directly next to an adjacent freed block. What I mean is that with a memory distribution that obeys our predefined criteria, the memory will continue to obey the criteria if only allocate is called. What’s more, when an offending case is created, it will be directly related to the block being freed. Thus, when freeing a memory block, if the freed-block merges with all freed-neighbors such that our criteria is maintained, then the system will have fufilled its goal.

Replacing heap entries of neighboring free-blocks requires the linked-list entry to maintain a pointer to its heap counterpart. The heap entry which already maintains a memory pointer must also maintain a pointer into the Linked-List to update its Linked-List entry’s pointer when the heap block is moved. This is all too complicated, so a cleaner way is to expand the meta data of a memory block to implement the Linked List (this way the heap entry only stores one pointer).

Given that the address of a free block is the location of Block-Start. One can obtain the addresses of both adjacent blocks in constant time like so:

Next Block:

- The Size of the Block(S) can be obtained as: S = mem[address-1]

- The End of the Block(E) can be obtained as: E = address + S

- The Address of the Next Block(N) can be obtained as: N = E + 3

Previous Block:

- The End of the Previous Block(E) can be obtained as: E = address - 3

- The Size of the Previous Block(S) can be obtained as: S = mem[E]

- The address of the Previous Block(P) can be obtained as: P = E - S

Since the Linked-List/Memory stores both allocated and free-blocks, we need a way to identify only free-blocks that need to be merged. Allocated blocks aren’t managed by the free-heap, so its ‘heap-position’ metadata holds no meaning. Luckily, there is a special heap location that cannot be pointed to by a memory block; the first entry in the free heap is metadata indicating the end of the heap so no free-block should point there. We can then use the heap pointer to seperate allocated blocks by forcing all allocated blocks to point to the start of the heap.

Once we’ve identified all the neighbors that are free-blocks, we need to replace their heap entries with a singular heap entry that spans the entire region. For simplicity, this can be done by first removing all adjacent entries from the heap, then adding a new entry. As the heap must not have any holes, to delete an entry from a heap one must move the end of the heap into the gap created by the deleted entry, and then sink/swim the entry now at the filled location depending on its size. Then a new entry can be added in the standard way.

Another thing, rather than allocating from the biggest free-block. It is better to allocate from the smallest free-block larger than the requested allocation size as this maintains a higher population of larger blocks. While descending down the heap cannot guarantee the smallest block, it can generally guarantee something close is found. Moreover, as this action starts from the root of the heap, it still ensures that if space is available allocation will succeed.

Padding

There is one last slight optimization. Most memory allocation algorithms are implemented with an extra parameter for the desired alignment of the data. One reason for this is that if a memory block contained a list of structures of stride 6 word, to retrieve the kth structure would require retrieving the 6 entries starting at k * 6 + block_address and reinterpreting them as the desired structure. But if the block address is 6 word aligned, the entire buffer can be casted as a buffer of the structure, and no reinterpretation is necessary. Thus, a better allocation call can be defined like this.

1 | uint Allocate(uint count, uint stride) |

The original size parameter is deconstructed into two parameters, count and stride, where size = count * stride. Additionally, the address we return should be in terms of stride, so our original raw address = new address * stride, that way the caller doesn’t need to concern itself with raw-addresses which it won’t use. To certify that this new address is valid, we’ll need to make sure that the raw address is divisible by our stride. We’ll do this through padding.

Padding in this case will refer to unused memory that exists to offset memory blocks to a desired alignment. The tricky part is the amount of padding we’ll need depends on the address of the memory block. Looking through the free heap entails that the size of the requested allocation will change depending on the free-block address. This is expensive and awkward, so a constant allocation size can be defined as such alloc_size = (count + 1) * stride which guarantees that a free-block capable of holding alloc_size is large enough regardless of its address alignment.

Once an adequate free-block has been located, the amount of padding necessary will be defined like so padding = (stride - (Raw Address % stride)) % stride. A second modular is added so that no padding is present when the Raw Address is perfectly aligned. Then the returned Address can be obtained like so (Raw Address + padding)/stride.

One would also have to return the raw address as a handle because ‘Free’ only recognizes the raw address.

Address Buffering

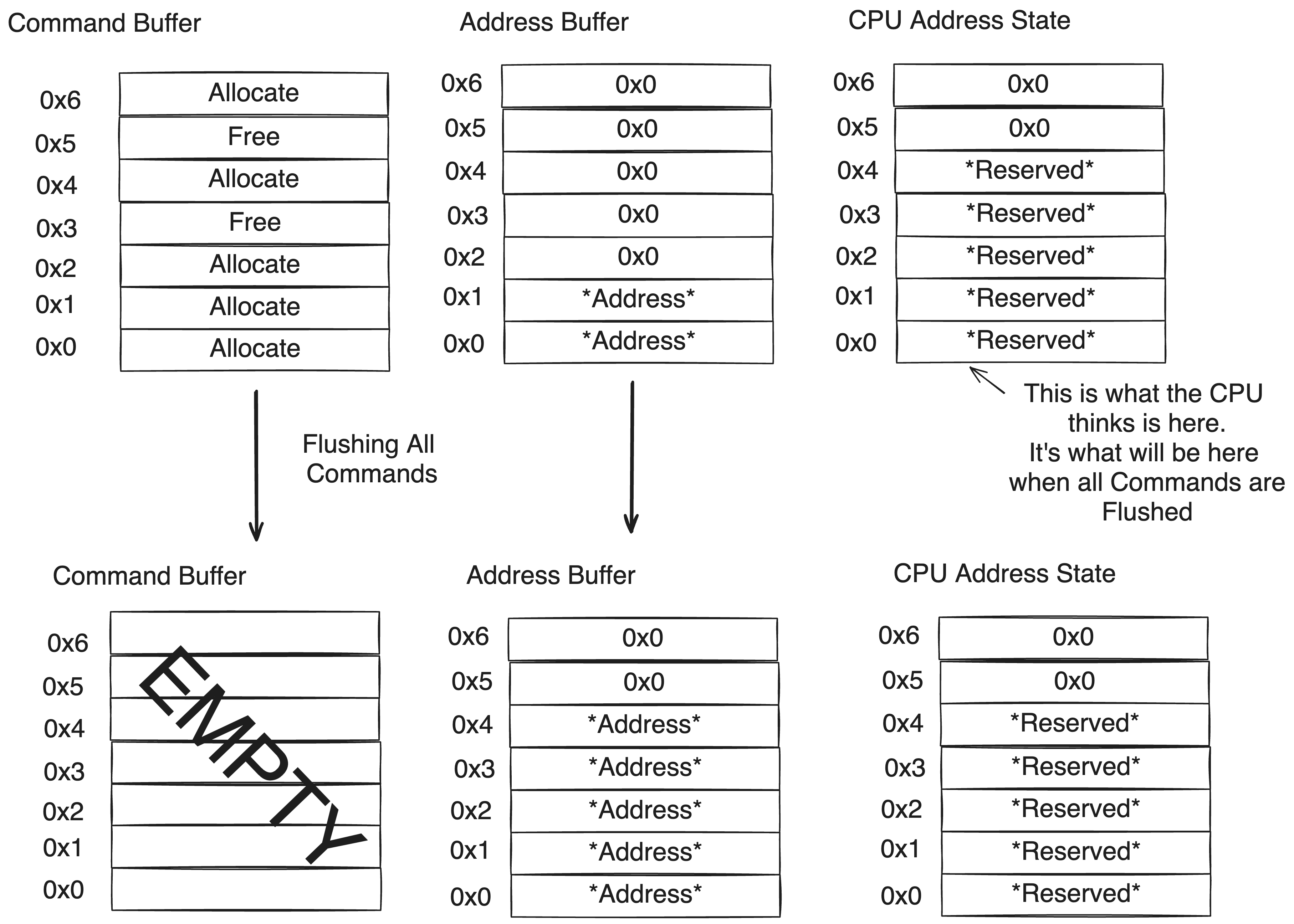

As it stands, ‘Allocate’ allocates a block in memory and returns an address, but where does it return to? The command for ‘Allocate’ and ‘Free’ are buffered into GPU execution, so neither really are ‘called from’ a very accessible place.

Like most compute shaders, we can retrieve the output of our operation by binding a seperate shader resource(a buffer) and having ‘Allocate’ write the address to the buffer. To write to or read from the memory block, this buffer can be shared with different shaders which first access the buffer to read the address to locate the information within our memory. Additionally, ‘Free’ would have to read from this buffer to determine which address to free.

On the CPU-side, the CPU can request a seperate buffer from the GPU for every memory ‘Allocate’ request but this is less than optimal. Doing this requires many Malloc requests sent to the GPU(possibly fragmenting its base memory) and the CPU to juggle a GPU-BufferHandle for every memory block. What’s more, each buffer is only one element in length–hardly worth a seperate memory block.

As each buffer contains a single address, a better solution is to define a single buffer which can hold all addresses created through our custom Allocate. The CPU cannot retrieve the direct addresses in the buffer(as the command itself is being buffered), but it does know the order in which the commands are given. Thus it can predict which entries are open and occupied, and instruct the GPU to fill an address that should be open by the time the instruction is executed. The CPU can then bind the reserved index in this buffer, where the address will be read to, to other shaders which can then determine the actual address by reading the address from the buffer at that index, which will be present when the command is actually executed.

Code Source

Optimized HLSL Parallel Implementation Allocate

1 |

|

Optimized HLSL Parallel Implementation Free

1 |

|